There’s an interactive you-be-the-journalist game at the Newseum in Washington, D.C. in which you race against another team to pull together the front page of a newspaper by answering sticky questions about what’s ethical and what’s not.

I’m thinking about this game because I’m thinking about the controversial police photo of pop artist Rihanna that leaked two days ago. The searingly tight shot shows Rihanna’s face with welts and bruises that were made, it’s widely speculated, at the hands of R&B star Chris Brown the night before the Grammy Awards.

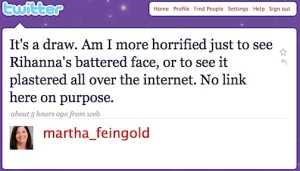

As with a lot of news these days, I first learned about Rihanna’s beating through Twitter, and when TMZ.com posted its prize photo, I learned about that through Twitter as well, when someone I follow tweeted the link to TMZ.com.

This case offers a striking reminder about how little we need an interactive game at the Newseum to play a journalist, because social media lets us do that in countless ways large and small every day. In the past, the public at large would scrutinize a decision by a media outlet on whether to show the photo. Now, we are faced with a similar dilemma ourselves as we decide whether to tweet, retweet, use a Facebook status update or write a blog post to link to or embed such a controversial photograph.

Gawker addressed the journalistic ethical gray area by outing the publications that ran the photo (outlets that included Gawker), calling the photo a “media ethics lightning rod.” What about the rest of us? Shouldn’t this also be a social media question? I didn’t tweet or retweet the photo, and I’m not linking to it anywhere here — which means I can’t link to TMZ.com at all, since the photo is still on its homepage. But does that matter? I looked at the photo the second I saw that tweet — and if I had read a news story that didn’t publish the photo or include a link, I would have Googled it.

I think it’s also interesting to note that this was not the only controversial image that made headlines this week. The New York Post ran an editorial cartoon that appeared to compare President Obama to a chimp shot dead by police. I was at home sick for three days this week so I watched a lot of cable news shows, and it seems that just about every show invited guests on to talk about the issue — and rightly so. The publication of the Rihanna photo, though obviously widely covered, received far less critical attention. I didn’t see guests brought on to weigh in on the controversy, and I think it was a missed opportunity to discuss domestic violence and how media outlets handle — or avoid — the issue. Were we more interested in seeing this red-hot celebrity exposed in such a vulnerable position than we were in what made a man think he had the right to do that to her?

Earlier this week, a friend of mine tweeted this of the Rihanna story:

I’m really getting tired of intelligent men I know saying, ‘I wonder what RiRi did to set him off like that.’

That’s the kind of honest discussion we need around domestic violence (and MTV News does a fine job getting into it here). It would be nice to see more of it on national media outlets, but if we don’t see enough there, the power of social media is that we can make sure it happens ourselves.

Photo credit: Gawker.com